Farewell

- Updated: January 1, 2022

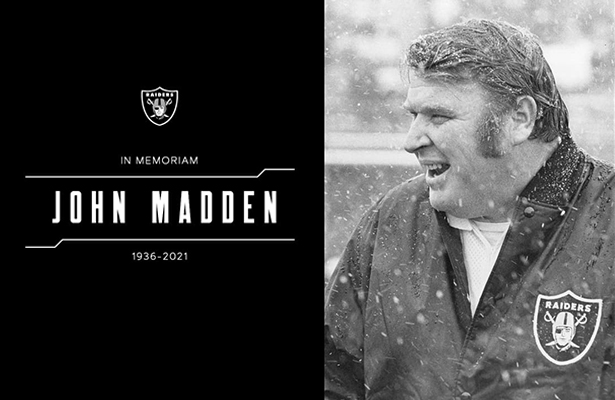

John Madden, the Hall of Fame coach-turned-broadcaster whose exuberant calls combined with simple explanations provided a weekly soundtrack to NFL games for three decades, died Tuesday morning, the NFL said. He was 85.

The league said he died unexpectedly and did not detail a cause.

Madden gained fame in a decadelong stint as the coach of the renegade Oakland Raiders, making it to seven AFC title games and winning the Super Bowl following the 1976 season. He compiled a 103-32-7 regular-season record, and his .759 winning percentage is the best among NFL coaches with more than 100 games.

“Few individuals meant as much to the growth and popularity of professional football as Coach Madden, whose impact on the game both on and off the field was immeasurable,” the Raiders said in a statement, hours before team owner Mark Davis lit the Al Davis Torch in honor of Madden, the first person to ever light the torch on Oct. 16, 2011.

“Tonight I light the torch in honor of and tribute to John Madden and Al Davis, who declared that the fire that burns the brightest in the Raiders Organization is the will to win,” Mark Davis said.

It was Madden’s work after retiring from coaching at age 42 that made him truly a household name. He educated a football nation with his use of the telestrator on broadcasts; entertained millions with his interjections of “Boom!” and “Doink!” throughout games; was an omnipresent pitchman selling restaurants, hardware stores and beer; and became the face of Madden NFL Football, one of the most successful sports video games of all time.

“Today, we lost a hero. John Madden was synonymous with the sport of football for more than 50 years,” EA Sports, the brand behind the Madden franchise, said in a statement. “His knowledge of the game was second only to his love for it, and his appreciation for everyone that stepped on the gridiron. A humble champion, a willing teacher, and forever a coach. Our hearts and sympathies go out to John’s family, friends, and millions of fans. He will be greatly missed, always remembered, and never forgotten.”

Madden was the preeminent television sports analyst for most of his three decades calling games, winning an unprecedented 16 Emmy Awards for outstanding sports analyst/personality and covering 11 Super Bowls for four networks from 1979 to 2009.

“People always ask, ‘Are you a coach or a broadcaster or a video game guy?'” Madden said when was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2006. “I’m a coach, always been a coach.”

It was a sentiment echoed by Hall of Fame president Jim Porter in his statement Tuesday night.

“He was first and foremost a coach,” Porter said. “He was a coach on the field, a coach in the broadcast booth and a coach in life.

“The Hall of Fame will forever guard Coach Madden’s legacy. The Hall of Fame flag will be flown at half-staff in his memory.”

Madden started his broadcasting career at CBS after leaving coaching in great part because of his fear of flying. He and Pat Summerall became the network’s top announcing duo. Madden then helped give Fox credibility as a major network when he moved there in 1994, and he went on to call prime-time games at ABC and NBC before retiring after the Pittsburgh Steelers’ thrilling 27-23 win over the Arizona Cardinals in the 2009 Super Bowl.

“John Madden was an iconic figure, transitioning from a successful coach to one of the most impactful and distinctive broadcasters in history, across all genres. His love of football was only matched by the fans’ admiration for him. He will forever be synonymous with the game,” said James Pitaro, chairman of ESPN and sports content for The Walt Disney Company. Madden worked for ABC Sports from 2002 to 2005 as an analyst for Monday Night Football.

Burly and a little unkempt, Madden earned a place in America’s heart with a likable, unpretentious style that was refreshing in a sports world of spiraling salaries and prima donna stars. He rode from game to game in his own bus because he was claustrophobic and had stopped flying. For a time, Madden gave out a “turducken” — a chicken stuffed inside a duck stuffed inside a turkey — to the outstanding player in the Thanksgiving game that he called.

“Nobody loved football more than Coach. He was football,” NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said in a statement. “He was an incredible sounding board to me and so many others. There will never be another John Madden, and we will forever be indebted to him for all he did to make football and the NFL what it is today.”

As Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones said, “I am not aware of anyone who has made a more meaningful impact on the National Football League than John Madden, and I know of no one who loved the game more.”

When Madden retired from the broadcast booth, leaving NBC’s “Sunday Night Football,” colleagues universally praised his passion for the sport, his preparation and his ability to explain an often-complicated game in down-to-earth terms.

Al Michaels, Madden’s broadcast partner for seven years on ABC and NBC, said working with him “was like hitting the lottery.”

“He was so much more than just football — a keen observer of everything around him and a man who could carry on a smart conversation about hundreds and hundreds of topics,” Michaels said. “The term ‘Renaissance man’ is tossed around a little too loosely these days, but John was as close as you can come.”

For anyone who heard Madden exclaim “Boom!” while breaking down a play, his love of the game was obvious.

“For me, TV is really an extension of coaching,” Madden, who also became a best-selling author, wrote in “Hey, Wait a Minute! (I Wrote a Book!).”

“My knowledge of football has come from coaching,” he said. “And on TV, all I’m trying to do is pass on some of that knowledge to viewers.”

Madden was raised in Daly City, California. He played on both the offensive line and defensive line for Cal Poly in 1957 and 1958 and earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the school.

He was selected to the all-conference team and was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles, but a knee injury ended his hopes of a professional playing career. Instead, Madden got into coaching, first at California’s Hancock Junior College then as defensive coordinator at San Diego State.

Al Davis brought him to the Raiders as a linebackers coach in 1967, and Oakland went to the Super Bowl in Madden’s first year in the pros. He replaced John Rauch as head coach after the 1968 season at age 32, beginning a remarkable 10-year run.

With his demonstrative demeanor on the sideline and disheveled look, Madden was the ideal coach for the collection of castoffs and misfits that made up those Raiders teams.

“Sometimes guys were disciplinarians in things that didn’t make any difference,” Madden once said. “I was a disciplinarian in jumping offsides; I hated that. Being in bad position and missing tackles, those things. I wasn’t, ‘Your hair has to be combed.'”

The Raiders responded.

“I always thought his strong suit was his style of coaching,” quarterback Ken Stabler once said. “John just had a great knack for letting us be what we wanted to be, on the field and off the field. … How do you repay him for being that way? You win for him.”

And boy, did they ever. Many years, the only problem was the playoffs.

Madden went 12-1-1 in his first season, losing the AFL title game 17-7 to the Kansas City Chiefs. That pattern repeated itself during his tenure; the Raiders won the division title in seven of his first eight seasons but went 1-6 in conference title games during that span.

Still, Madden’s Raiders played in some of the sport’s most memorable games of the 1970s, games that helped change rules in the NFL. There was the “Holy Roller” in 1978, when Stabler purposely fumbled forward before being sacked on the final play. The ball rolled and was batted to the end zone before Dave Casper recovered it for the winning touchdown against the San Diego Chargers.

The most famous of those games went against the Raiders in the 1972 playoffs at Pittsburgh. With the Raiders leading 7-6 and 22 seconds left, the Steelers had a fourth-and-10 from their 40. Terry Bradshaw’s desperation pass deflected off either Oakland’s Jack Tatum or Pittsburgh’s Frenchy Fuqua to Franco Harris, who caught it at his shoe tops and ran in for a Steelers touchdown.

In those days, a pass that bounced off an offensive player directly to a teammate was illegal, and the debate continues to this day over which player it hit. The catch, of course, was dubbed the “Immaculate Reception.”

Oakland finally broke through with a loaded team in 1976 that had Stabler at quarterback; Fred Biletnikoff and Cliff Branch at wide receiver; tight end Dave Casper; Hall of Fame offensive linemen Gene Upshaw and Art Shell; and a defense that included Willie Brown, Ted Hendricks, Tatum, John Matuszak, Otis Sistrunk and George Atkinson.

The Raiders went 13-1, losing only a blowout at the New England Patriots in Week 4. They paid the Patriots back with a 24-21 win in their first playoff game and got over the AFC title game hump with a 24-7 win over the hated Steelers, who were hampered by injuries.

Oakland won it all with a 32-14 Super Bowl romp against the Minnesota Vikings.

“Players loved playing for him,” Shell said. “He made it fun for us in camp and fun for us in the regular season. All he asked is that we be on time and play like hell when it was time to play.”

Madden battled an ulcer the following season, when the Raiders once again lost in the AFC title game. He retired from coaching at age 42 after a 9-7 season in 1978.

Madden was a longtime resident of Pleasanton, California, a Bay Area suburb.

A 90-minute documentary on his coaching and broadcasting career, “All Madden,” debuted on Fox on Christmas Day. The film featured extensive interviews that Madden sat for this year. His wife, Virginia, and sons, Joseph and Michael, also were interviewed for the documentary.

John and Virginia Madden’s 62nd wedding anniversary was two days before his death.